In 1797 the Atlantic slave trade is at its peak but soon Europeans will abandon it one by one and turn to other means of stripping resources from West Africa. The other major force of change is European colonialism. The decision will reverberate through generations and Condé makes no clear statement as to whether Dousika’s choice was right, wrong or inevitable and therefore no choice at all. Most Bambara – including the king and his other advisers – are deeply suspicious of Islam and look down on Dousika when his son’s secret is revealed, but Dousika sees an opportunity to make strategic alliances through his son. The first dent in that fortune is the oldest son Tiekoro, who is intrigued by the newly arrived religion Islam – and in particular the access to knowledge that is provided by learning to read and write, a necessity in Islam that is forbidden for the rest of the Bambara (who make up the majority of Segu’s population).

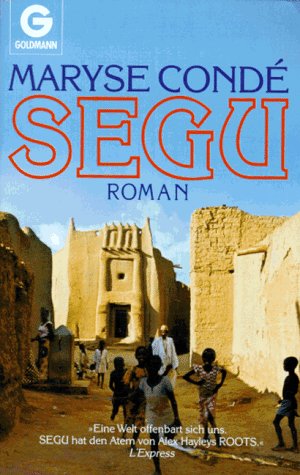

(I have already forgotten whether he also has daughters, which I think speaks to how generally the women in this book are barely mentioned, though a few do get a bigger role.) They are wealthy, with a large home and money to pay the fetish priests to ensure the continuation of their good fortune. Dousika Traore, trusted adviser to the king, has four sons by his various wives and concubines. Though they don’t all stay there, allowing the family saga to become epic in what it encompasses. Segu by Maryse Condé (translated by Barbara Bray) follows one family in the city state of Segu, in what is now Mali. I started this book in August for Women in Translation Month, but it turns out that historical epics take a while to read and even longer to process.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)